It can be tricky to get a clear picture of your finances when you’re living away from home for the first time. This student budget spreadsheet will help you to make your student loan last and see where the money goes. It will help you for life…

I’ve spent the past few weeks talking to several hundred students on creative courses from locations all around the UK on the topic of how to make your loan last.

During the workshops, several students made the comment that they wish loans were paid-out in a more piecemeal fashion – a regular drip-feed on a weekly or monthly basis.

I think this is a fairly savvy point, which probably would help more students avoid the (inevitably) bad financial decisions we all make at some point during study. However, part of the point of higher-education is equipping you with the skills for life and, chief among them, critical thought and self-reflection.

In this sense, the loan is one of many, sometimes painful, learning curves that are part of that experience. It also strikes me that it’s not a bad rehearsal for life in the creative industries.

A dry run

Most creative workers are freelancers and most of us get paid in occasional lump sums, rather than the more steady incomes that would enable us to emulate a salary.

In this sense, making the three payments of a student loan last across the year, while topping it up with other forms of income (drawing on savings, part-time work, frantically selling your things etc.) is a pretty good emulation of the cash-flow peaks and troughs we encounter in creative work.

I’ve been using a student budget spreadsheet to illustrate to students how they might spread their loan out and get some clarity on their financial position throughout the year. I thought I would share it on here, too, along with a few pointers on how to use it, which is really the important bit.

Please note: You won’t be able to edit the master sheet on this link, so it’s important that you save a copy to your own Google account or download it for use with Excel before you try to edit it.

You’ll note there are three tabs: Spreading your loan, What have I got? and What do I need?

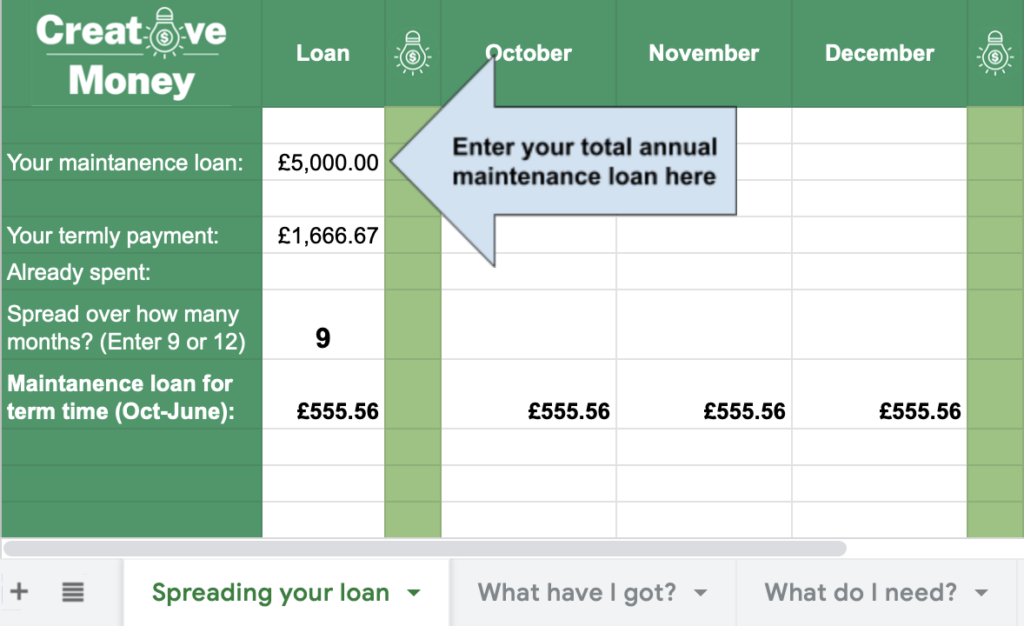

Step 1: Enter your annual maintenance loan

Start on the first tab (Spreading your loan) and enter your annual loan amount where indicated.

When you enter this figure, the sheet does a very simple calculation to split the payment into three, indicating how much you will receive in payment each term.

It also divides your annual figure equally across either 9 or 12 months (depending on your selection in Box B7).

Choose 9 months if you expect to be relatively ‘bill-less’ over the summer period – for instance, you know you’re heading home and won’t need to supplement your income at that point.

If you’re planning on renting throughout summer, then go for 12.

The amount you have to contribute towards your living costs each month is then displayed in row 8: ‘Maintanence loan for term time (Oct-June)’.

This will prove useful later.

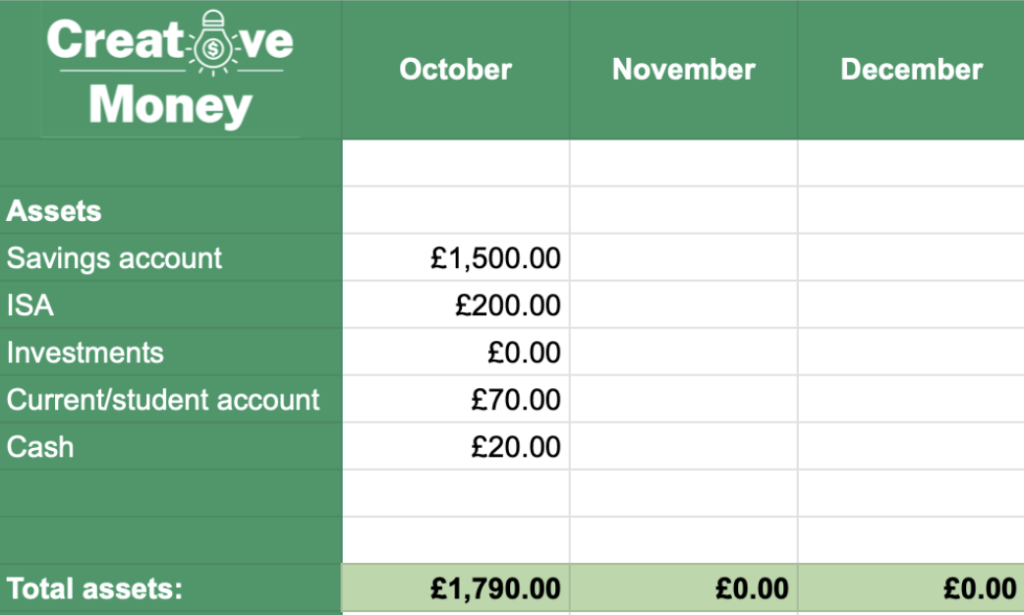

Step 2: Figure out what you have

Next, head to the What have I got? tab. This is where you take a snapshot of your financial position. This is best done once a month at the same time each month, e.g. the first of the month.

Log anything you’re holding in your savings accounts, in cash, or other investments and things that hold some worth and could be converted to cash.

(As a rule, avoid listing your ‘stuff’, as selling your guitar etc. is usually a last resort).

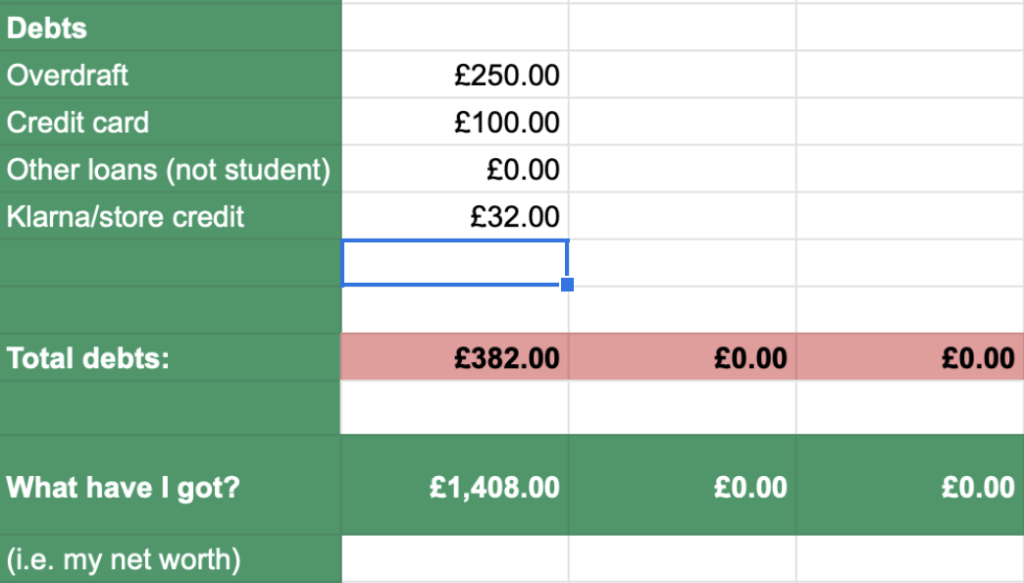

Below you can list any debts you might hold, perhaps your overdraft, credit card and store credit.

The sheet then deducts your assets (what you have) from your liabilities (debts/what you owe) and tells you what’s left.

This figure is known as your net worth, but is probably best thought of as ‘What have I got?’ hence the title…

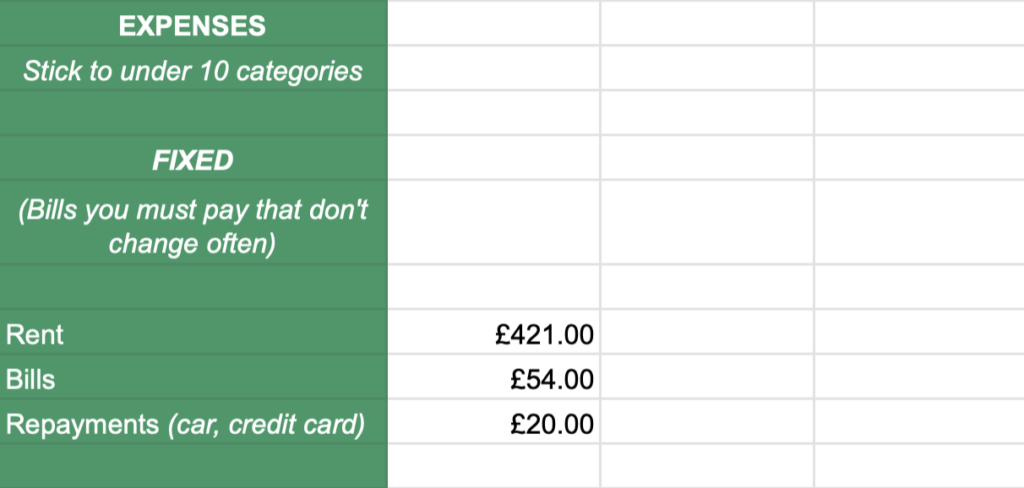

Step 3: Enter your income and expenses (predict then review)

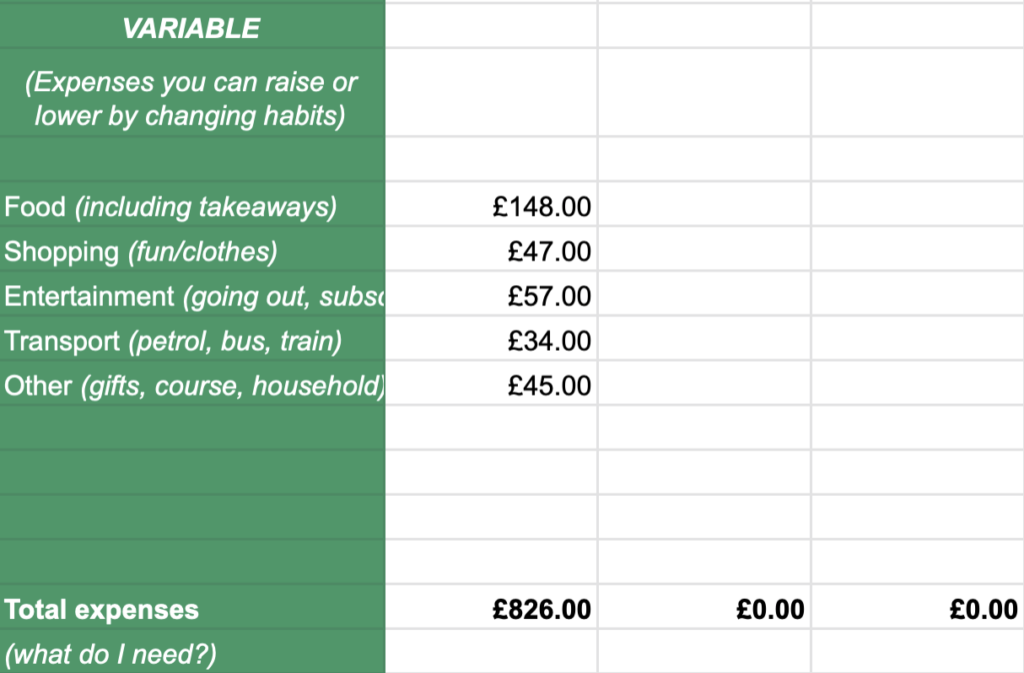

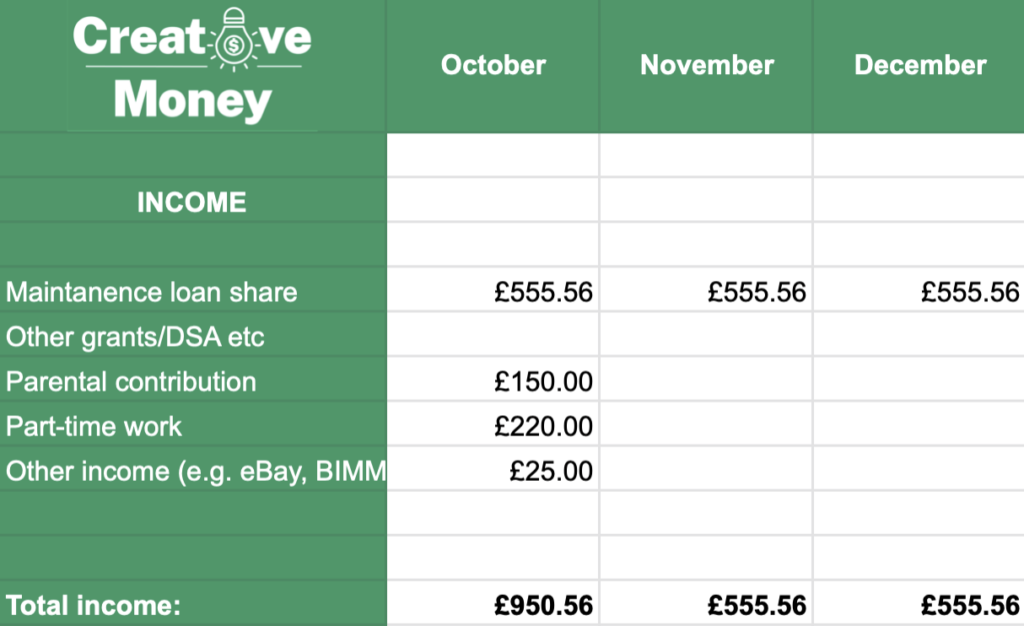

Now move to the What do I need? tab. This is where you capture the movement of your money in and out of your accounts for the month: your cash-flow.

Do not comb your statements line-by-line to do this. Use a budgeting app, which does the legwork for you and will automate the monthly totals for expense categories.

Once a month, open it up, drop the expense total from each of your main app categories into the relevant column on the ‘What do I need?’ tab and you’ll start to get a very clear picture of where your money is going (and how much of it is going there!) each month.

(You can of course use the apps themselves to compare monthly spending, but I find it’s clearer if you drop them on the sheet.)

Do the same thing with your income.

This is where that student loan calculation from Step 1 comes back in. The sheet pulls through your student loan portion for the month (calculated on the ‘Spreading your loan’ tab) and adds it at the top of the income column.

It’s not strictly ‘income’ but it can be thought of as such while you’re a student…

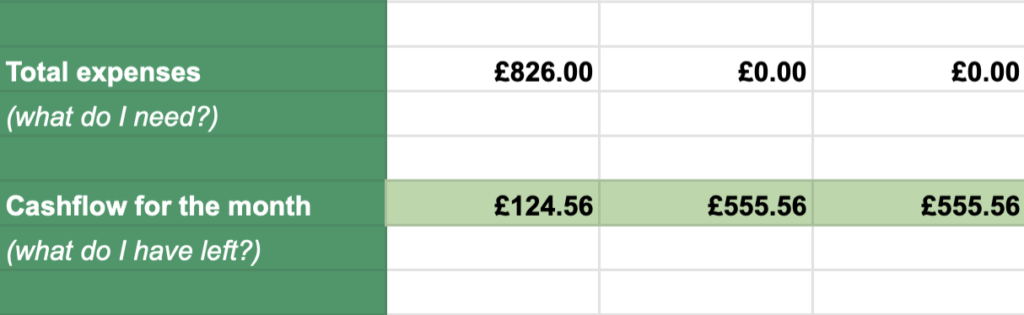

The sheet will tot up the categories to tell you your total expenses (Row 40: What do I need?) and then deduct your expenses from your income to show you your cashflow for the month (Row 43).

If the figure is positive, you’re spending less than you’re bringing in, great!

If it’s negative (which it may well be during study) and continues to be, you’ll need to do something to either lower your expenses or raise your income, so take action!

Step 4: Tracking is the key to success

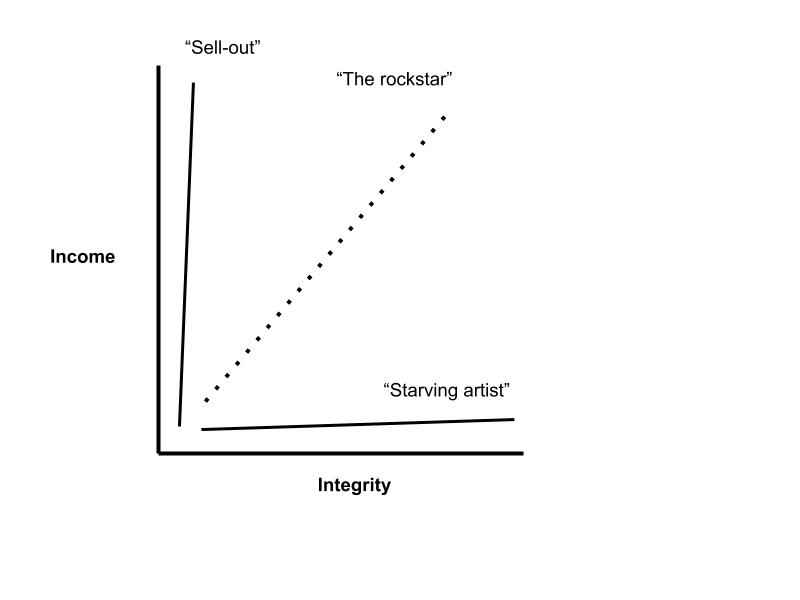

A lot of people will tell you that budgeting is the key to keeping your finances in shape as a student and beyond. But this is only true if you accept the reality of your expenses – and most people don’t.

More often than not we create a budget from numbers we’ve plucked from the sky. Our perception of these costs is often very different from the reality, which means we inevitably ‘break the budget’, tell ourselves off and then get demotivated and give up on it.

Budgets should change. Don’t feel bad about it.

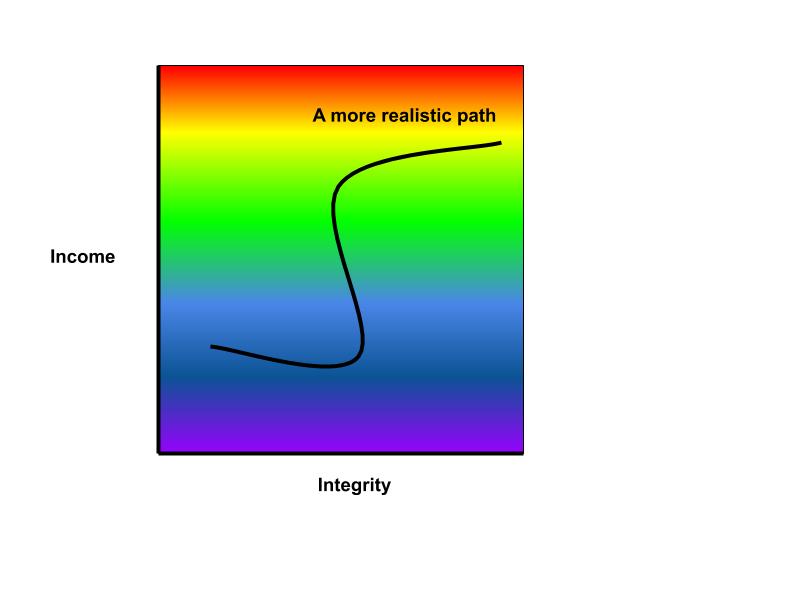

The secret to budgets (that is often not discussed) is this: Success with this stuff depends more on reflection than prediction. It is the tracking that makes the difference.

Budgets should change. It is not about chucking some numbers on a spreadsheet and hoping they’re right, it is accepting that it is a guide and it won’t ever be 100% right, then periodically checking and correcting your assumptions.

If you use an app to track your expenses and update the sheet once a month, you’ll have a much better sense of your real expenses. You can then use that information to make more realistic decisions about what to budget for the next month – and so on.

You don’t have to wait until the end of the month either. The apps often allow you to setup running totals.

For instance, you might set a limit of £100 a month for food shopping. Every time you check in on the app, it will tell you how far through that figure you are for the month – and you can adjust your spending accordingly.

Step 5: Repeat this once a month. Don’t spend ages on it.

I always tell people not to spend a long time doing this.

It should be just a case of nipping through and dropping any totals from the 10 or so spending categories on your app into your sheet. Then the balances from the accounts on your ‘What have I got?’ tab.

If you’ve kept things tagged-up on the app throughout the month, this should take you a maximum of 10 minutes.

It doesn’t need to take a long time. In fact, it is much better if it doesn’t. You want this habit to stick, not become a chore.

Talking to yourself

Once you’ve pulled the info together, give yourself a moment to look over things on the sheet. Ask yourself the following questions:

- Is there anything unexpected or surprising about the month’s spending? Why is that?

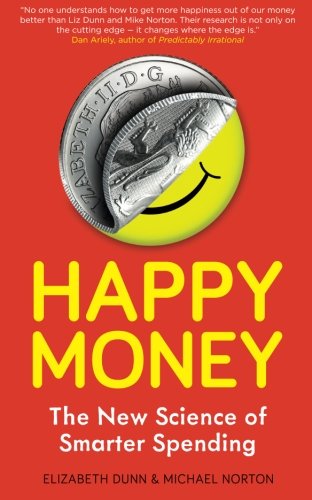

- What was worth the money? (It made you genuinely happier, or had some considerable or lasting benefit)

- What really wasn’t worth the money? (It was a waste, or had very short-lived benefits)

- How does my spending compare to the previous month?

- Is my ‘What have I got?’ number (Net worth) going up or down?

This should take you about another 10 minutes. But to be on the safe-side, let’s say the whole process should take you 30 minutes a month.

That’s just 30 minutes a month to get clarity on how much you have, where the money is going and whether you’re on a good course, or need to make some changes.

Don’t waste time agonising over decisions you’ve already made or getting forensic in your analysis of micro transactions. We’re looking at trends and overall direction here.

Spend just a little time putting these habits in place now and you’ll reap the benefits for the rest of your life.