Back in November, I launched a series of online workshops at music colleges across the UK, the aim of which was to help creative students to better manage their money.

The idea being that if they can figure it out during their studies they might have an easier time while in education and start their professional lives on a stronger footing. As a result, I have spoken to students from Manchester to Brighton, London, Bristol and Birmingham. It’s been really interesting to see how this stuff connects with people.

“I always ask people who come to the workshops what financial education they have received. The most common answer is ‘I haven’t had any.”

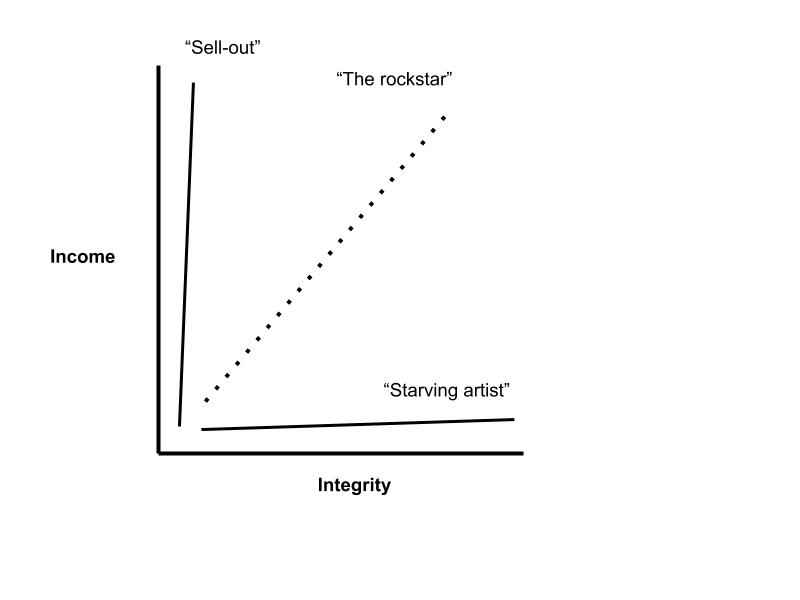

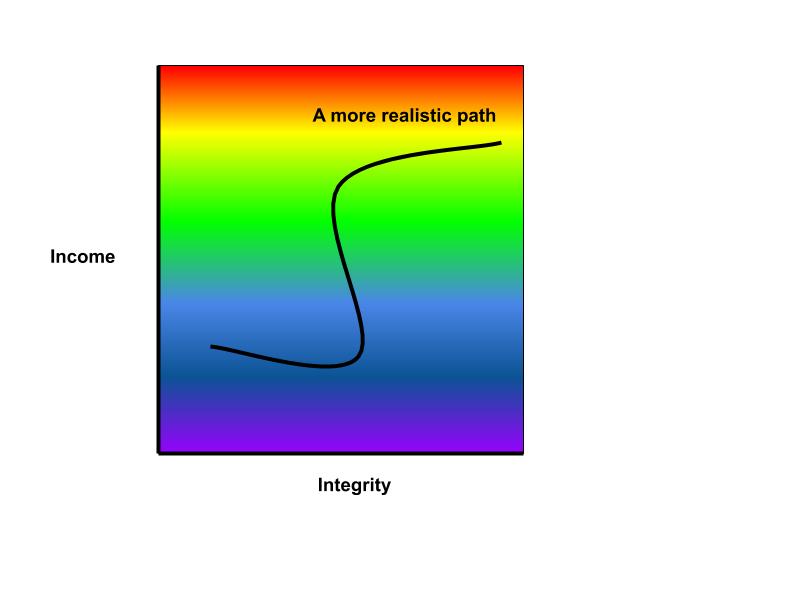

Like many of us, I am what you might optimistically call a ‘multi-hyphenate’ freelancer. Alongside my main role in music journalism, I also spend a day a week teaching budding music/media types and I do Creative Money stuff about one day a fortnight. The workshops have felt like a good way to bring all these threads together.

What’s more you learn pretty quickly as a tutor that your knowledge is highly subjective. So, with the first iteration of the workshops, I tried to be a good listener. Now, as I go into the second run of these workshops, I’ve been pondering some of the main points I’ve learned from the first run. Here’s what I’ve found…

1) Fix the cause, not the behaviour

It probably won’t come as a surprise that students worry about money, however, the proportion still surprised me. An astonishing 71% worry about making ends meet, according to Save The Student’s annual money survey. Money gets quite intertwined with our emotional state sometimes and many of them tell me that they have experienced anxiety when checking their balance.

I can get on at them about using a budgeting app, but if someone feels they can’t check their balance in the first place, it’s not going to help. Instead, I’ve realised that helping people to think about the causes of that anxiety (be it self-judgement, role models, or a simple knowledge gap when it comes to money) needs to take priority before you can change those behaviours.

2) We still have a major issue with financial education

I always ask people who come to the workshops what financial education they have received. While a few have had some tips from parents, the most common answer is ‘I haven’t had any.’ Again, Save The Student’s annual money survey backs this up, with the vast majority (71%) saying they wish they’d had a better financial education.

Martin Lewis has made some good strides in partnership with Young Enterprise and this stuff is now on the secondary curriculum, but it seems it’s still potluck when it comes to the depth and resources devoted to the topic by different schools.

The majority of the young adults and adults in this country (i.e. those with almost ALL the earning and spending power) have had no financial education outside of the ‘university of life’, ‘school of hard knocks SON’ etc. Talk about the blind leading the blind…

I have written before about the fact that you can not be inherently bad with money – most of the time we’re just not educated. However, the more I consider the lack of educational infrastructure around this utterly essential topic, the more the situation strikes me as completely insane. And that’s before we try to get our heads around the misbranded student loan system…

3) Location matters

Because I am A COOL GUY, I surveyed students at the beginning and end of the five week course. They were asked to gauge agreement or disagreement with a number of statements, for instance, “I know what to do if I run out of money.”

One thing that struck me was that students in London and Brighton were noticeably more anxious about their finances. Those students’ biggest gains in the course came from alleviating anxiety points. For instance:

- “I am confident avoiding or getting out of debt” = 50% increase

- “I know what to do if I run out of money” = 68% increase

- “I worry about running out of money” = 46% decrease

- “I feel anxious about student debt” = 53% decrease

While I’m pleased to see the course helped them, I think it’s telling that they made noticeably greater gains in these areas than their counterparts in Manchester.

Of course, many students already consider living expenses when picking a university, but the numbers would suggest that those in places like Manchester were generally happier about their finances.

Given money’s ability to affect everything from our mental health, to our diets, relationships and even our ability to focus on education, the financial impacts of the location are worth serious consideration when picking a place of study.

4) Most of them know much more than I did

I was not great with money at university and I had good financial role models around me.

“The students I meet rate far, far lower on the ‘financial tool-o-meter’ than I did at their age. This is a good thing.”

My typical day at university went something like: wake up too late to make breakfast. Eat a disappointing plastic sandwich on the way to my lecture. Sit through engage fully with a lecture and seminar. Break for lunch (baked potato from the canteen). More lessons. Go to the pub. Eat a gigantic cheeseburger. Drink. Go to another bar. Drink. Give £20 to one of a series of guys with suspect nicknames. Order pizza. Fall asleep in front of the DVD menu of Alan Partridge.

Essentially: it was the best of times, it was the worst of times. My approach was fun and fairly typical, but the consistency of it was, err, sub-optimal…

The current generation have only known the world, post-financial crisis, and are aware of the need to not-be-tools when it comes to money. Even if they haven’t got all the answers, they’re taking this stuff seriously because they have been left without the comfortable cushions of fully functioning welfare, healthcare and employment opportunity enjoyed in the previous two or three decades.

The students I meet rate far, far lower on the ‘financial tool-o-meter’ than I did at their age. This is a good thing.

5) The best solutions are the simple ones

Many people think learning to handle their finances will be a dangerous combination of the complicated and the mind-numbingly boring. It doesn’t need to be either. People can be suspicious of simple principles, but my experience thus far has told me they tend to work best because it makers them much easier to communicate, adopt and turn into habit.

Once you can address the causes of your financial behaviour, the basic solutions to any financial goal almost always comes down to the following…

- Track your net worth, income and spending

- Find a way to spend less than you earn

- Save or invest the difference

Tracking your net worth might sound fancy but it is essentially just asking ‘What have I got?’ (i.e. your cash, savings and investment balance minus your debts) once a month and noting the total.

There’s an abundance of apps that can track your spending and income without demanding you switch accounts. Then, once you know what you’re spending, you can see where the fat is and trim accordingly, making way for that burgeoning savings habit.

Sometimes I tell people how I go about the above and I can see them switch off, as if it’s too simple or obvious to be really helpful. It needs to be simple, though, or we don’t do it, at least not consistently. To the doubters, I ask, “But are you really doing all of this?” Most are not. Keep it simple, students – and everyone else, too…

Want me to talk to your students about running their personal finances? Get in touch!

Creative Money Blogs include principles, resources and opinion pieces relating to personal finance for creatives.