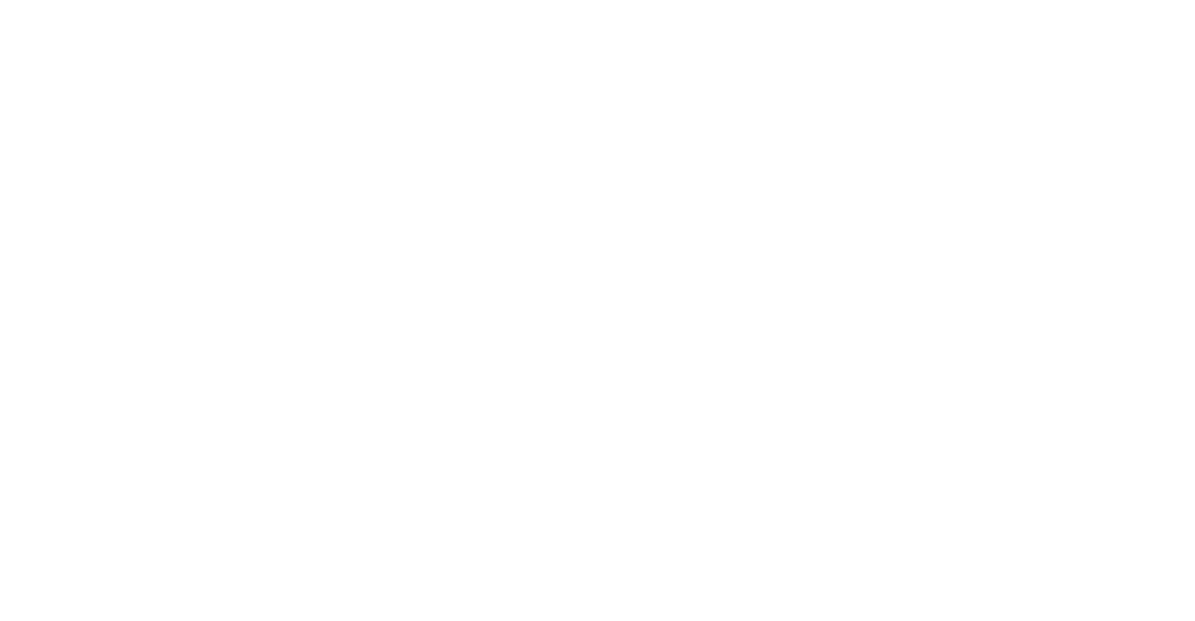

Our thoughts on the financial outcomes of life as creative workers often seem to fall into two categories: ‘the starving artist’ and ‘the sell-out’. If only it were that simple…

I would wager that everyone who earns money from creative work has wondered at some point whether or not they’re ‘selling-out’. The tropes at the heart of this struggle are are within us all: the starving artist has unimpeachable integrity but negligible income, while the sell-out picks their gigs by the paycheque. They remain locked in combat, fighting for our very souls.

We’ve all likely had cause at some point to embrace the starving artist and some of us even come to experience life at sell-out end of the scale – gaining a full understanding of the ambiguous privilege of considerable wealth and fame.

Sometimes, we may also consider the evener rarer ‘third way’, wild success on our own terms – let’s call this ‘the rockstar’ – but this often seems even further removed from our view of the achievable (though Seth Godin’s The Icarus Deception argues the opposite).

At other points, we may feel we have no option but to leave an industry, or take some other work on in purely to pay some bills.

Anyone who’s even come near to experiencing true poverty knows that the starving artist cliché is a false romance

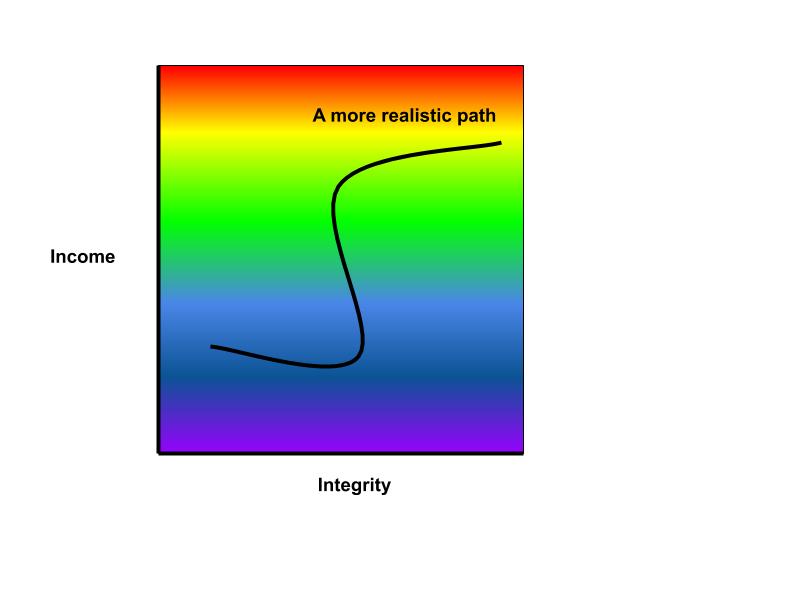

What’s interesting is the extremities of these viewpoints – that we seem to ascribe the myriad outcomes of our creative work as an ‘all or nothing’ endeavour. The truth of it, though, is that it is a spectrum – and that existing on that spectrum, rather than at one of two extreme poles, is not such a bad place to be.

Anyone who’s even come near to experiencing true poverty knows that the starving artist cliché is a false romance. It’s been perpetuated throughout history, often by patrons in positions of wealth, but while understanding or experiencing poverty and the broader human condition has no doubt informed great creative work, it is certainly not a route to happiness. In fact it is, by definition, a direct route to unhappiness.

What’s it worth?

At the other end of the scale, it is widely acknowledged that while wealth can help you ‘buy’ a certain level of happiness, the benefit of greater wealth tails-off dramatically once you’ve covered your basic needs and a few extra comforts. This is a phenomenon that US blogger Mr Money Mustache has popularised and termed the Marginal Utility of Money.

Want to make sure you never miss a post?

Sign up to the Creative Money newsletter!

Let me read it first >

Even Warren Buffett, the 89 year-old billionaire CEO of Berkshire Hathaway – and at one point the world’s richest person – counsels against the pursuit of wealth for its own sake. And this is a guy who bought his first shares aged 11.

“Doing reasonably well in this country really is pretty darn good,” he said, talking to US students in 1999. “Great wealth is the tiniest bit different, in a real sense, than having just a decent income. To trade a decent income and something you love doing… for huge wealth where you trade a lot of your principles would be a terrible mistake.”

So, if we agree that both extremes are flawed and stop trying to define our financial personalities against a minority of outliers, what does the right path actually look like? And what’s a reasonable income?

Great wealth is the tiniest bit different, in a real sense, than having just a decent income

Warren Buffett

That is yours to decide. For me, it’s enough to cover living expenses, to be able to pay for a few home comforts and holidays and to save enough to retire within the next 25 years (WHAT!?) At the more luxurious end, I’d like to spend as little time on compulsory work as possible. I like my work, but I value freedom even more.

Figuring out the numbers behind these goals is really useful to making sure you’re actually on course to meet them.

I discussed why tracking your spending is key to understanding your cash flow (and therefore getting some control over a variable income) last week, but there are other benefits to that process, too. When you know how much you spend, you know how much is enough. You know when you can stop, or say no.

As far as possible, I’d also like to get to these points above without doing work that I do not personally believe in.

Don’t do dogma

A line from our recent How I Make It Work interview with freelance journalist Lydia Wilkins sticks with me here.

“‘At the end of the day, you only have yourself to answer to.’ Regardless of having to pay your bills, keep to deadlines… if it ‘sits right’ – then that’s okay.’”

If you operate with integrity, then you avoid selling-out yourself, but only you can judge what that might look like.

The ‘starving artist’ trope comes from a belief system and, as with any belief system, there will always be a vocal minority of hardliners, who refuse to question the dogma out of some fear that the world will unravel. Instead, each of us needs to decide on our personal beliefs and principles around money and creativity – and make decisions accordingly.

There’s a broad, rich spectrum between ‘the starving artist’ and ‘the sell-out’

If you lean towards the starving artist axis then, contrary to the thinking of many, you’ll likely need to watch your expenses closely. What’s more, planning for the future and times of poor cash flow becomes even more essential.

If you lean the other way, gaining a higher income, then you may have more flexibility with your spending and insurance against the risks you take (some of which might pay-off handsomely). However, to gain true satisfaction from your work, you will likely still need some measure of your personal values built-in to it – lines you don’t cross. This might be to do with the ethics of the organisations you work with, the relative creative appeal of jobs etc. Knowing your values helps you to navigate the path.

For instance, in my case, I am open to many different types of work. My main gig is music journalism, but I’ve written copy and advertorials, I’ve run events and managed projects, I’ve led degree courses and taught. But I’ve come to understand that if the only reason I want to take a job is the money – and I can find no other appealing features in terms of the work, my personal or career development, or the organisation I’m working with – then I am going to regret that decision.

Not everyone will feel that way – or feel they have the option to do so (particularly right now) – but that’s OK. Indeed, that’s the whole point. Creative Money is not here to promote the pursuit of untold riches, but simply to help you figure out how you can sustain yourself over the long term as a happy, creative person.

There’s a broad, rich spectrum between the tired clichés of the starving artist and the sell-out. Where do you want to be?

Creative Money Blogs include principles, resources and opinion pieces relating to personal finance for creatives.

How can we help you?

What issues are you facing? What questions do you have about managing your money in the creative industries? What would be most helpful to you?

We don’t have all the answers, but maybe we can find someone that does.